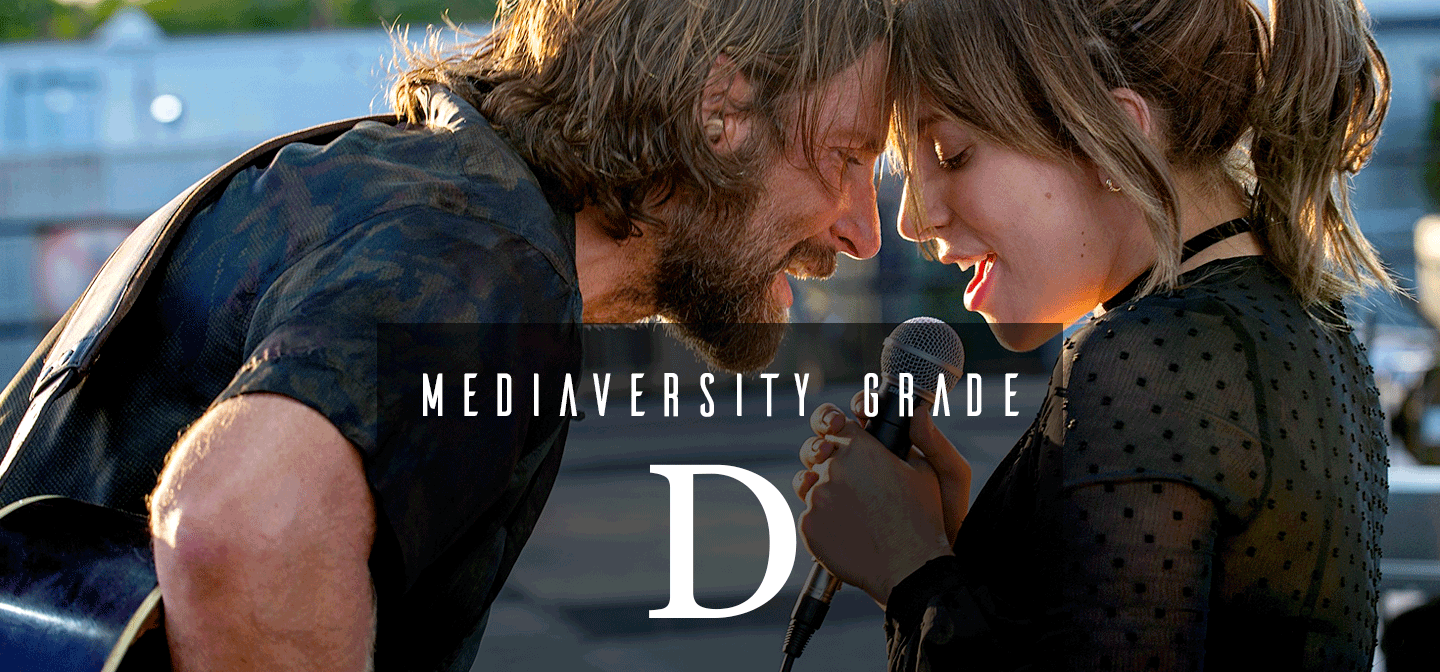

A Star is Born

“I’m not quite sure if A Star is Born is supposed to be a tragic love story or an examination of an abusive relationship.”

Title: A Star is Born (2018)

Director: Bradley Cooper 👨🏼🇺🇸

Writers: Screenplay by Eric Roth 👨🏼🇺🇸, Bradley Cooper 👨🏼🇺🇸, and Will Fetters 👨🏼🇺🇸 based on the original story by William A. Wellman 👨🏼🇺🇸 and Robert Carson 👨🏼🇨🇦🇺🇸

Reviewed by Li 👩🏻🇺🇸

Technical: 3.75/5

This summer, A Star is Born triumphantly strode out of film festivals like Venice and TIFF to a resounding chorus of delight. Rolling Stone found Bradley Cooper’s directorial debut “near perfect” and Vanity Fair has already called it “the Oscar movie to beat.” Even my Twitter feed of progressive critics generally copped to enjoying the movie, so by the time I headed into theaters I thought the movie would be a solid bet. Perhaps my expectations were too high, because I wound up disappointed.

At face value, the raw performances by Cooper and Lady Gaga do impress. Visceral cinematography and dramatic sound mixing give this film a sparkling, new-car sheen. But beneath the lacquered surface, I found myself increasingly bored by its long-winded premise: the meandering collapse of a drunken country star, and the poor sap who stood by him the entire way down. Along with said poor sap, Ally (Lady Gaga), I dutifully sat through the messy descent of Jackson (Bradley Cooper), all the while hoping to glimpse more backstory to the supposed, titular star. Yet Ally never truly gets “born,” despite the film’s misleading title. She stays pinned beneath her husband’s embarrassing shadow and rather than coming into her own at any point, she merely fades into a whisper of herself until even her last song of the 137-minute ramble is dedicated to the man.

It’s this antiquated, male-centric mood of A Star is Born that took me out of the film entirely. Between a glaring lack of modern touchpoints—who in 2018 watches the Grammys?—and the deeply problematic gender dynamics, I felt like I was watching a stale time capsule.

I haven’t seen the three previous versions of A Star is Born, but when you realize the story originated in 1937, it makes a lot of sense. Jackson might condescendingly bang on about the necessity of “having something to say” in one’s art, but ironically, this fourth remake of an unchanged premise has nothing new to say at all.

Gender: 1/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? NOPE

Going into the film, I made the mistaking of thinking Ally would be the main character. Instead, A Star is Born follows the trajectory of Jackson and employs an unflinching male gaze that’s evident through the idolization of Ally as a moldable ingenue, seen through flashes of Ally’s naked body and, most tellingly, in the film’s utter lack of interest in Ally’s interior world.

Under this lens, the relationship between Ally and Jackson emerges as a twisted and emotionally abusive tale that’s tangled up in icky power imbalances. For starters, Ally is isolated in a world of men. She meets Jackson against a backdrop of drag queens, yes, but beyond that glimpse of sisterhood, she gets tossed around like a hot potato between her father, her boss, her agent, or her husband Jackson, each of them mansplaining Ally’s talent to her as they domineer and leach different things from her. In fact, the only man who supports Ally unequivocally is her friend Ramon (Anthony Ramos), but his character is flat and sees little screen time.

As for the relationship between Ally and Jackson, I assumed this 2018 film would give an empowering a figure like Lady Gaga the kind of agency she deserves. Instead, she’s supremely powerless. Once Jackson “discovers” her in a dive bar, he controls her every move. He has his driver stalk Ally while she’s in the middle of working a shift, to the point where she gives in and quits her job—a scene posited as a glorious “fuck you” to her shitty boss, but in reality, would be a setback to her financial independence. Once Jackson’s driver takes her on a private jet and plants her backstage like a groupie, Jackson tricks Ally into coming onstage to perform, announcing her to thousands of screaming fans and thereby stripping her from any plausible choice of declining. Not that she doesn’t try; Ally panics and says she doesn’t want to do it, over and over again. But Jackson steamrolls her and she winds up onstage only to love it, proving that, of course, he was right all along. Even as Gaga’s phenomenal voice shakes the theater, the otherwise powerful scene is undercut by the implicit message that it takes manipulation, coercion, and the circumventing of consent in order to do what’s best for a naive woman.

As if their early romancing wasn’t already tinged with weird power dynamics, there’s little evidence of relationship-building as Ally and Jackson purportedly fall in love. All we’re left with is the vague sense that their attraction is based on two-way fetishization—Jackson sleeping with a young protegée who he only covets when she performs the genre of music he likes, and Ally sleeping with a celebrity who can kickstart her career. By the time we’re down the ugly side of the mountain, Jackson’s substance abuse rearing its head in ever-increasing amounts, Jackson has the gall to gripe that Ally has “lost herself” by making pop music with backup dancers. In a particularly uncomfortable scene, Jackson calls Ally over in the midst of celebrations over the release of her first album, only to grab her behind the neck, lock eyes, and reiterate his schtick about “having something say” and how she can’t “lose herself,” as if dying her hair is a slippery slope to becoming fake. The previous smile drops from Ally’s face, and all that’s left is a chilling tableau of a man intimidating a woman through a death grip on her neck.

At no point do we understand whether or not Ally even likes the pop music she’s making. Her perspective is so irrelevant to the film’s exploration of Jackson’s drug addiction and character implosion, that Ally is turned into mere symbol for various men to control.

In short, I’m not quite sure if Ally and Jackson’s marriage is supposed to be a tragic love story, or an examination of an abusive relationship. Worst of all, the movie never critiques Jackson’s behavior. Ally makes excuses for him, calling his drug abuse a disease and desperately repeating that his reprehensible behavior is “not his fault.” Well, it is his fault—and it’s disappointing to watch the film ignore the more intriguing character of Ally in favor of humanizing a destructive and insecure man.

Race: 2/5

Characters of color are intentionally cast into positive roles, but from a narrative standpoint, they’re blips in the film’s laser focus on Jackson. Women of color are frustratingly ignored: I can only recall one family scene, where Jackson’s father figure Noodles (Dave Chappelle) hosts dinner, during which his Black, light-skinned wife and daughter speak a line or two apiece.

Meanwhile, the men of color occupy the trope of being magical saviors who swoop in to help white characters in their times of need. Puerto Rican actor Ramos plays Ramon, Ally’s friend, and he’s there to pick up the pieces after each colossal fuck-up by Jackson. Noodles appears in a late cameo, literally picking up Jackson’s comatose body off his front lawn after yet another bender.

I can understand the friendship between Ally and Ramon—coworkers whose solidarity has been forged in the thankless fires of food service—but the film never shows us why Noodles would bother to mentor Jackson. It tells us a backstory, sure; but it isn’t particularly believable. The ensuing scene of Jackson, quickly sobered up and surrounded by Noodles’ family, thus rings false. After all, what do these well-adjusted people care about an entitled celebrity who snips guitar strings off their instruments in order to make showy, impromptu marriage proposals to strangers who waltz into their home, looking for their wayward boyfriends?

Bonus for LGBTQ: +0.25

Cameos by popular drag queens like Shangela and Willam constitute some of my favorite moments of the movie. But their Otherness is clearly used as a way to present Ally as progressive, similar to the way Jackson’s relationship with Noodles feels like a device to make Jackson seem “down.”

That said, given Gaga’s longstanding allyship with the LGBTQ community, their inclusion feels more grounded than the obvious box-ticking of ethnic diversity exhibited through Noodles. And while I found their scenes all-too fleeting, some queer critics express positive reactions to the way Jackson treats the queens as people, rather than sideshows. GQ’s Brennan Carley writes, “It's a small victory, maybe, but a hell of a win for the drag community.”

The queens never really come back after that Ally’s first performance, and that’s a shame because this film really could have used a little more joy and effervescence.

Mediaversity Grade: D 2.33/5

By all means, go and enjoy A Star is Born. Cooper and Gaga bare their souls in this film, and that level of vulnerability is brave and laudable. But know that its 1937 story goes wholly unchallenged and can be discomfiting to watch in certain scenes, especially given these current times where, much like Ally, women continue to be controlled by broken men with too much power in their hands.