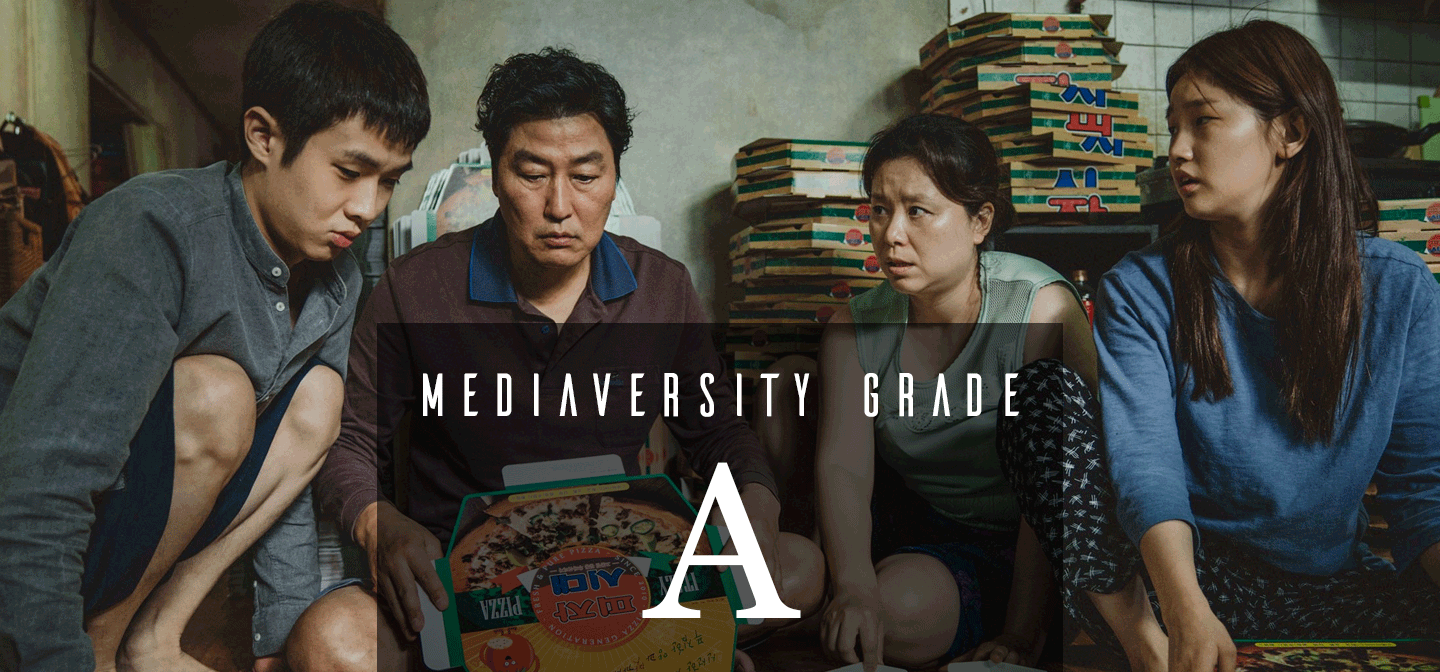

Parasite

“Parasite exudes cultural specificity, with deep cuts to Korean headlines and reality TV shows.”

Title: Parasite (2019) / Korean: 기생충

Director: Bong Joon Ho 👨🏻🇰🇷

Writers: Jin-Won Han 👨🏻🇰🇷 and Bong Joon Ho 👨🏻🇰🇷

Reviewed by Elaine 👩🏻🇺🇸

Technical: 5/5

Director Bong Joon Ho returns to Korea for his latest film, and the move has paid off. The Palme d’Or-winning Parasite presents a more intimate affair than the hijinks of his last film, Okja, but packs no less of a punch thanks to its ambitious construction. Centered around the poor family of the Kims, who inveigle themselves into the upper-class home of the wealthy Parks, Parasite surprises with thrills, laughs, and thoughtful social commentary.

Parasite glides like a lethal shark without an ounce of fat. Each visual detail, each beat of its unrelenting pace exists to serve the film’s purpose. Bong spent years developing the story, which originated as a play—a fact evinced by the intentional staging of each frame. The extremely wide aspect ratio grabs your attention from the opening shot of the Kim family's sub-basement apartment. The Kims crowd into every scene together, their packed bodies emulating the junk crammed into their home’s narrow hallways. In sharp contrast, the rich Parks rarely share space within a frame. The wide angle of the camera emphasizes this lack of familial intimacy through the wealth of space they have in their modern, minimalist home. Scant opportunity exists for these disparate classes to come into contact, as Mrs. Park (Cho Yeo-jeong) underlines with an offhand comment about how she can't even remember the last time she rode the subway.

Kim Ki Woo (Choi Woo-Sik) bridges the gap, though, by becoming an English tutor to the Park family daughter, Da Hye (Jung Ji-so). He hasn't gone to university and he doesn't speak English very well, but it doesn't matter. He comes from a family of hustlers, and a trusting Mrs. Park soon accepts him with open arms and an open wallet, setting off a chain of events that Bong twists in careful and darkly madcap ways.

It quickly becomes apparent that the Park home eclipses the Kims’ in more ways than one. Oft-collaborator Hong Kyung-Pyo (Snowpiercer and Mother) returns as cinematographer and has created a completely unique vocabulary of light to subtly enhance these differences—from the sallow fluorescents of the Kims’ apartment to the clear, unfiltered brightness of the Park home and later, to dank and subterranean depths.

A huge fan of director Kim Ki-young and his 1960 film The Housemaid, Bong also stresses the importance of stairs in this film. As a sign of affluence for Koreans, the verticality symbolizes the ability to afford a multi-level home. In Parasite, Ki-woo climbs flights of stairs to leave his neighborhood, and even coming into the Park’s home, the camera swings upward with Ki-woo’s gaze to reiterate how he has to ascend to reach it. Just as key, if not more so, are the moments when characters in the film descend. The stairs, visually and as a metaphor, work double duty to represent the futile struggles of the lower class to rise above their station.

Bong wields plenty of other metaphors too, and not a single one feels superfluous. Parasite presents more than a technically tight story though, and the expert handling of characters gives it its emotional heft. Furthermore, while the story threatens to fly off the rails at several points, Bong somehow takes all of the details he sprinkles throughout and wraps it up with pathos and genuine empathy in the last act. The script crackles, and you can expect the usual wacky and dark humor of Bong paired with a mastery of form. You never know what could happen next, but you’re confident in his hands no matter where the story leads.

Gender: 4.5/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? YES

In the midst of a raging flood, Ki Woo and patriarch Ki Taek (Song Kang-ho) struggle to salvage important items from their destroyed home, but the family’s daughter Ki Jung (Park So Dam) casually lights up a cigarette while sitting on a toilet lid that spews sewage everywhere. It’s a mood, and I love it. Parasite’s women, including Ki Jung, are multi-faceted and serve themselves rather than a dominating male presence. Ki Jung exudes level-headed coolness and remains unfazed at the bad cards (or sludge water) the world deals her. Rather than believe the house always wins, she uses her smarts and swagger to propel her family forward using whatever means necessary.

Her mother, Choong Sook (Jang Hye-jin), is equally complex and plays a dominant role as head of the family, in partnership with her husband. A former shot put champion, her framed silver medal takes up one of the few places of honor in the home. Bong has previously showcased athletic women in his movies, like the archer of The Host, and Mrs. Kim indeed flexes the muscles in the family. Even when her husband play-fights with her, no one takes it seriously because the entire family knows that mild-mannered Ki Taek would lose out to the matriarch.

As for the Parks, the first word we hear used to describe Mrs. Park in Parasite is “simple,” but that’s only in the eyes of those who don’t bother to dig deeper. While naive, her character reflects her social status as someone who has never been given a reason to distrust anyone. Mr. Park belittles his wife due to her lack of skill as a traditional homemaker in cooking and cleaning, but her genuine compassion comes from wanting the best for her family.

One of Parasite’s few detractions for its portrayal of women, however, comes from their sparse interaction. Mrs. Park talks to the Kim women, but their conversations primarily center around Mr. Park and their young son, Da Song (Jung Hyun-jun). Also, these exchanges only accent the imbalance of power between them since Mrs. Kim and her daughter Ki Jung occupy subservient positions. A later exchange between Mrs. Kim and the previous housekeeper of the house, who also plays a multi-faceted role, pits equal wills in a far more interesting manner, adding another decisive tally in Parasite’s favor.

Race: 5/5

The first Korean film to win the Palme d’Or, Parasite’s satire on class struggles could speak to many countries but probes South Korea especially. Last year, Lee Chang-dong’s Burning similarly addressed societal struggles of the disenchanted youth in the country, and the rage that simmers below the surface at their impotence. But in Parasite, Bong hones in on income disparity, bringing the audience into poor Korean neighborhoods where the Kims’ sub-basement apartment is one of the norm, and where even the quality of light is different than where rich people live.

Bong’s previous two movies have starred Hollywood actors and featured multicultural filmmaking, but he really thrives back in his homebase. He unapologetically inserts South Korean cultural items that distinctly color the movie—from the luxury of the Parks’ pajamas to the Taiwanese Castella Cake disaster that led to bankruptcy for many. When Mrs. Park snacks on “commoner food” ramdon, it’s a deep cut back to the Korean reality show Dad! Where Are We Going?. Basically the culinary equivalent to breaking open a box of Easy Mac, a celebrity dad actually made it hip to dine on the instant noodle mishmash in a 2013 episode. And even when Ki Woo forges his documents to pretty up a resumé, it’s likely a sly dig at the recent Choi scandal, which also involved fraudulent credentials.

Although the details are South Korean, Parasite’s diversity goes beyond its embrace of cultural specificity. Its depiction of class also humanizes the characters in all their shades of gray, rather than creating caricatures in a class warfare movie. He allows us to empathize with both sides, regardless of their backgrounds.

Ki Taek, the father of the Kim family, does not lack skill nor is he lazy. In the opening scenes, he watches directions on YouTube once and then folds a pizza box with panache and speed. Later, he drives a car smoothly, taking corners without spilling his employer’s coffee from the cup. You get the feeling, more than once, that he and his family just needed a few breaks but never got them. However, the Kims aren’t bestowed the sort of saintlike status that films often slap on underrepresented groups, with the romanticization of difficult situations. Given the opportunity, the Kims don’t choose to sympathize with others of their class and instead fight tooth and nail over the scraps that the wealthy throw them.

Bong portrays two families that misunderstand each other and shows how that misconception leads to tragedy. Parasite is rife with impersonations: Each member of the Kims take on a persona to infiltrate the Park household, but the Parks also try on the idea of someone “lower” than them, whether it’s through eating ramdon or during sexual roleplaying. A first glance implies that the Kims are the film’s parasites, especially seeing how their names (Ki Taek, Ki Woo, Ki Jung, Choong Sook) are formed from the Korean translation of the film’s title, Ki-saeng-choong. They’re the ones that take advantage of their situation and live off their employers. However, the Parks also leech off of their servants and completely depend on them to enable their lavish lifestyle.

Mediaversity Grade: A 4.83/5

Bong has created a masterpiece that entertains as much as it provokes thought. Each meticulously crafted frame reveals as much in the background as in the foreground, and every little eye twitch holds significance. Parasite strikes just the right balance of sympathy and societal critique, without heavy moralizing. Despite its pointed jabs, Bong poignantly asks whether a future exists where we can better our situations as easily as we can climb a flight of stairs.