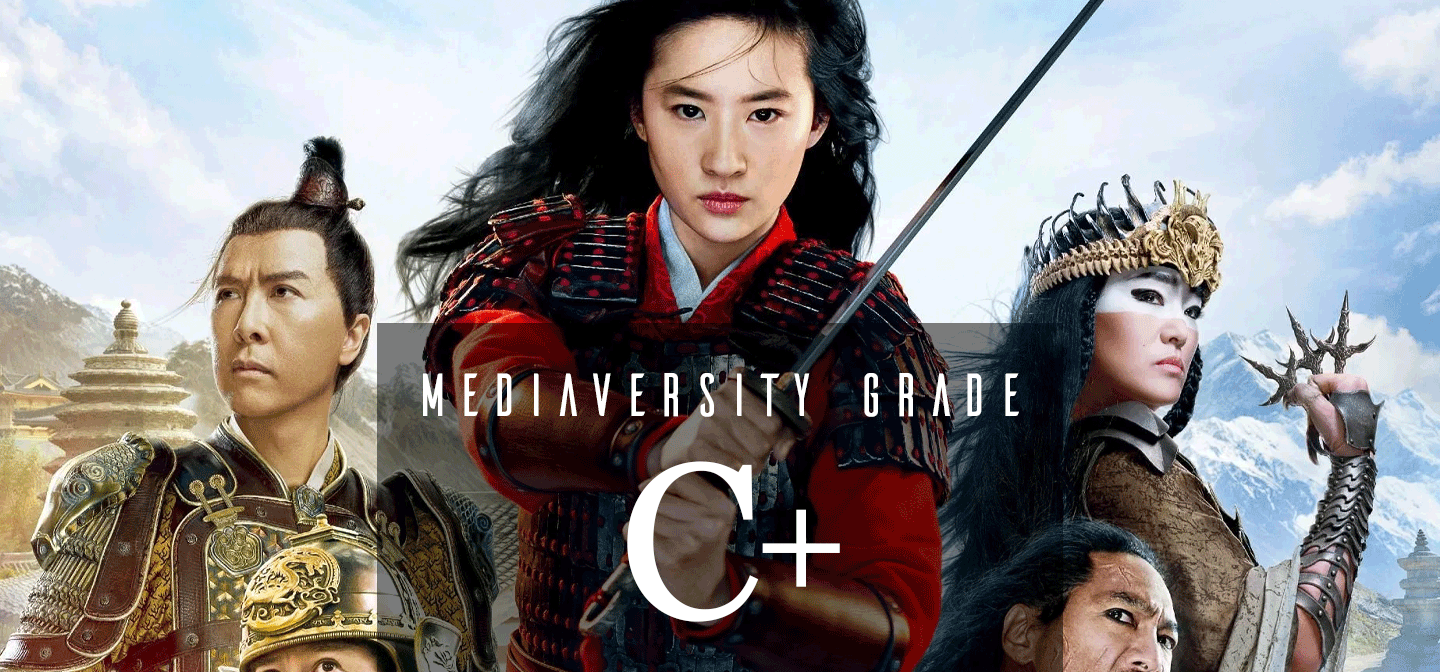

Mulan (2020)

“Who knew that an all-Asian cast could feel so disappointing on racial representation?”

Title: Mulan (2020)

Director: Niki Caro 👩🏼🇺🇸

Writers: Rick Jaffa 👨🏼🇺🇸, Amanda Silver 👩🏼🇺🇸, Elizabeth Martin 👩🏼🇺🇸, and Lauren Hynek 👩🏼🇺🇸

Reviewed by Li 👩🏻🇺🇸

Technical: 3/5

Months after Disney made its live-action remake of Mulan available to rent for an eye-watering $30, it’s now finally free to stream for folks with Disney+ subscriptions. Cue stragglers like myself coming in to see what all the hullabaloo was about.

Shop talk surrounding the film’s controversy has largely come and gone, so I’ll keep this review brief: I’d set my expectations low and therefore, I had a perfectly nice time taking in all the glitz and glamour that comes with a star-studded cast and $200 million production budget.

However, the film’s brilliant parade of color and Hong Kong-style action feels oddly soulless. Some dissonance stems from the 4th-6th century source material, a Chinese folktale titled the Ballad of Mulan that sees its heroine sacrificing everything to defend an autocratic emperor. Such an obedient soldier makes for a dull hero by American norms, where wariness of government is built into our DNA and idolized through such patriotic bangers as "Give me liberty, or give me death!" and “Let freedom ring!” A cowboy-maverick-anti-masker, Mulan is not.

On top of that, director Niki Caro and her team of screenwriters make it doubly hard to root for Mulan (Yifei Liu) by giving her natural-born abilities that eradicate the much more satisfying emotional journeys of hard work, cunning, and a good old fashioned underdog story. In 1998, Disney’s animated Mulan used no such superhero theatrics, and its character development felt all the stronger for it.

Finally, whiplash TikTok-style editing—with none of the fun irreverence—leaves no time for moments to resonate. The beautiful artifice of Mulan remains, yes, but don’t pull back the curtain because you’ll find nothing behind it.

Gender: 4/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? YES

Mulan might star a woman who infiltrates the army to prove that women can be warriors, but her end game still relies on gaining the approval of men: Her father (Tzi Ma), fellow soldiers, and the emperor (Jet Li) all stoke anxiety in Mulan who seeks to win them over. Rather than smash the patriarchy, Mulan validates these very same men who couldn’t see her value until she waved her magical abilities in their faces.

Sure, there’s an argument to be made for change coming from within a broken system. But when Mulan rejects a much more interesting offer to be mentored by the “witch” Xianniang (Gong Li), I couldn’t help but feel disappointed at seeing her dismiss an opportunity to grow and flourish outside of the confines of mens’ expectations altogether.

I suppose I should just be glad we’re following a female protagonist at all. And don’t get me wrong, that definitely goes in the “pro” column, especially given how Mulan isn’t the sole woman in a sea of men—something we still see in movies like the Tomb Raider series or standalone features Arrival (2016) and Gravity (2013). Instead, Mulan easily passes the Bechdel Test as she holds relationships with several women throughout the film, something screenwriters Elizabeth Martin and Lauren Hynek explicitly made a priority from the get-go.

In minor roles, we see her sister, mother, and the village matchmaker. And while her emotional story arc mostly centers her relationship with her father, the film’s most interesting pairing occurs between Mulan and the antagonistic, shapeshifting Xianniang (who doesn’t exist in the original poem—a welcome case of taking creative license with old material to suit modern needs.) Mulan and Xianniang’s similarities as powerful and ostracized women, combined with their opposing philosophies on morality, provide tension not unlike what you see between Rey and Kylo Ren in Star Wars.

Unfortunately, that potential is quickly squandered. Caro’s Mulan displays no appetite for ambiguity and instead punishes Xianniang as the flat villain she so clearly isn’t. Meanwhile, Mulan’s relationships with other women feel equally flat, appearing solely to prove that she’s “not like other girls”. Her silly sister screams at spiders; her mother forces Mulan into gender norms; and the matchmaker herself epitomizes outdated ideals of subservient femininity. In fact, nowhere do we see traditional presentations of femininity appreciated in the film at all. Adornments like makeup and womens’ clothing become the butt of visual jokes, whereas Mulan’s martial arts expertise and efficiency in killing a bunch of nomads become the traits that launch her into heroism.

In short, the representation of women onscreen feels mixed. But behind the scenes, it’s unequivocally great that a female director and three female screenwriters were placed at the helm of such a high-profile movie. While they hardly execute a perfect ten, the broader goal is for women to be allowed to produce something mediocre and not get punished for it during their careers. I genuinely hope this proves to be the case for Caro and team.

Race: 3/5

Who would’ve thought that an all-Asian cast could feel so disappointing on racial representation?

First, the papercuts: A white director working from a script written by four white screenwriters was already worthy of a passive aggressive, “Is this really such a good idea?” But not a dealbreaker on its own.

Then came the wallops. In August 2019, Mulan’s star, Yifei Liu, tweeted her support of the Hong Kong police at the height of their brutalities against pro-democracy protesters. By the time that firestorm had subsided, Mulan stepped in it again as audiences noticed in September 2020 that the film’s credits thanked propaganda departments in China’s western province of Xinjiang, where parts of the movie were filmed—and where horrific atrocities against Uighur Muslims, such as forced internment and sterilizations by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), continue to this day.

Knowing all this, I had hoped that a Disneyfied sheen of an American blockbuster could keep the grossness of Chinese authoritarianism at bay. But when faced with stunning desert-scapes and dramatic cliffs, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was observing the land of forcibly displaced communities.

Other jolts, like seeing actors who have publicly supported the CCP and by extent the party’s aggressions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, kept taking me out of the scene. Watching Donnie Yen as Commander Tung twirl a sword recalled his starring role as a martial artist in Ip Man 4 (2019), a movie whose chest-thumping nationalism and dog whistles like “we are all Chinese” took me by surprise. Even the incomparable Gong Li as Xianniang, the film’s best character by far, felt tainted given Li’s similar loyalties.

Thankfully, such lightning rods were tempered by the purer enjoyment of seeing Asian American stars like Hong Kong-born Tzi Ma or Southern California natives Jason Scott Lee as the villain Böri Khan and Rosalind Chao as Mulan’s mother. And when I glimpsed the film’s cameo of Ming-Na Wen, I gave a silent internal whoop. (The actress, born in Macau and raised in New York City, had voiced Mulan in 1998.)

I’d like to pause for a moment, however, to make it crystal clear that a) my critiques of the CCP hardly excuse the United States’ own dismal record on human rights, and b) I don’t think actors need to “be quiet” any more than I would wish for Colin Kaepernick to “keep politics out of sports.” On the contrary, I think it’s exciting when actors stand up for what they believe in. But as paying consumers, we’re well within our rights to avoid movies whose actors harbor political leanings we find repugnant. In my case, as a Taiwanese American who worries about the increasing number of CCP fighter jets soaring over the heads of her family members in Taipei and Kaohsiung, the shadow of Chinese influence on Disney’s 2020 remake of Mulan distracts from the escapism I seek in a feel-good movie.

Even from this vantage point, however, I can still appreciate the opportunities a huge project like Mulan has opened up for Asian American talent. It’s not the fault of individuals that Disney fumbled its appeals to the global theatrical market, or that studio heads missed the chance to hire much-needed authenticity in Mulan’s core creative team. (This thread by Chinese historian Xiran Jay Zhao hilariously recounts the many, many ways that Mulan makes no sense to people versed in actual Chinese culture.) More work and visibility for Asian American talent will always be great, and Mulan certainly accomplishes that goal.

Mediaversity Grade: C+ 3.33/5

With one hand grasping for China’s moviegoing audience, as the other refuses to let go of its American roots, Mulan collapses into confusion. And it still underwhelmed at China’s box office.

So between this remake and Netflix’s Over the Moon from a few months back, can we stop trying to lump together Chinese nationals and Chinese diaspora, and instead stick with movies that can actually appeal to both? Everyone loves a brainless action romp, for example. I’d gladly take The Meg (2018) over misguided pandering any day.