Moonfall

“Despite some well-executed diversity, Moonfall ultimately worships at the altar of white male ‘mavericks.’”

Title: Moonfall (2022)

Director: Roland Emmerich 👨🏼🇩🇪

Writers: Roland Emmerich 👨🏼🇩🇪, Harald Kloser 👨🏼🇦🇹, and Spenser Cohen 👨🏼🇺🇸

Reviewed by Li 👩🏻🇺🇸

Note: This review was commissioned by Lionsgate. The content and methodology remain 100% independent and in line with Mediaversity's non-commissioned reviews.

—MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD—

Technical: 3/5

Director-writer Roland Emmerich (The Day After Tomorrow, Independence Day) launches his comforting brand of everyman-against-the-world into outer space with his latest disaster movie, Moonfall. We follow a heroic trio of ex-NASA astronaut Brian Harper (Patrick Wilson), NASA’s acting director Jo Fowler (Halle Berry), and lunar conspiracist KC Houseman (John Bradley) as they go against the odds to combat a crashing moon. Or are they combating aliens? Wait no, they’re fighting bureaucracy—and technology, that’s a big baddie too. Okay, so the exact plot is beside the point; you just need to know that there are a lot of enemies in Moonfall and it’s up to Harper to save the world. The ensuing underdog story will surprise no one, so feel free to shut your brain off, enjoy the action (and almost camp levels of unscientific ludicrousness), and let cute scenes of Houseman’s cat, Fuzz Aldrin, warm the edges of this silly space romp.

Gender: 3.75/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? YES, but barely

Berry carries the weight of gender representation in Moonfall and does so with grace. As the only non-stereotyped woman in the film, her character hits every important point: A position of power as NASA’s top dog, at least after her male predecessor turns tail at the first sign of trouble. Fowler has her own sense of self, given a son to protect while her ex-husband, Department of Defense General Doug Davidson (Eme Ikwuakor), supports her from the ground. She also sees plenty of screen time, although her dialogue lags far behind that of her colleague Harper’s.

In smaller roles, Harper’s ex-wife Brenda (Carolina Bartczak) and Fowler’s hired nanny, a Chinese exchange student named Michelle (Kelly Yu), both follow more traditional routes as the caretakers of children, given only rare moments of “empowerment” that feels more like a consolation prize than anything else.

'Jimmy' (Zayn Maloney, left) and 'Michelle' (Kelly Yu, right). Photo Credit: Reiner Bajo

It’s not these women, though, that keep Moonfall from approaching gender equity. The film feels mired in the past thanks to structural narrative decisions. Fowler may make a great female lead, but she takes a clear backseat to the film’s true hero, Harper, who’s on a mission to prove himself to the world after unfairly falling from grace. It’s Harper, not Fowler, who is told by three separate characters that he is “needed”—needed by Fowler, as she entreats him to return to NASA. “We need you to join the fight,” says the good-guy aliens to Harper in a hallucination (just go with it), and in a late-movie denouement, Houseman confirms, “The world needs you.”

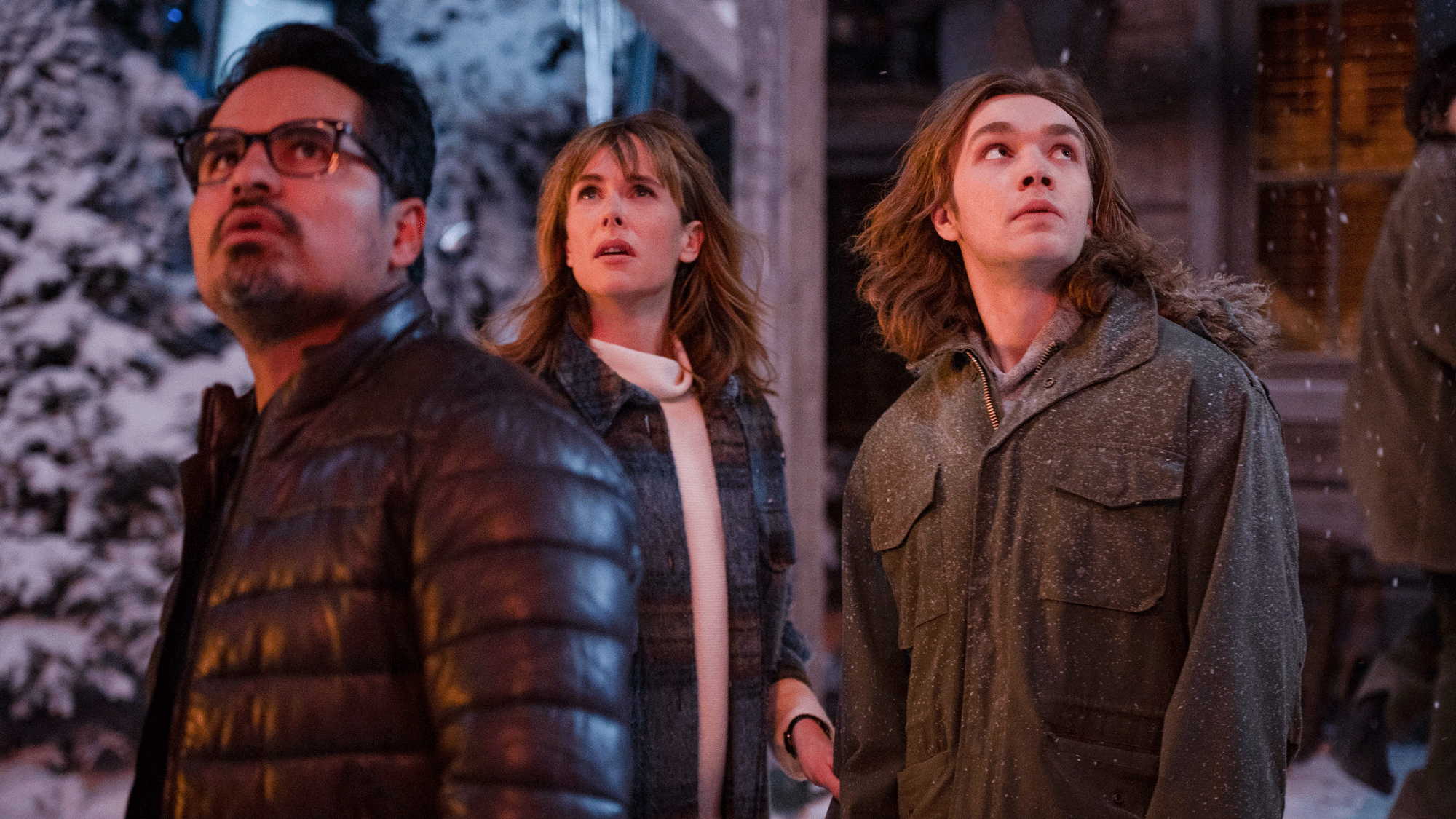

In this vein, men are the protectors, almost always positioned slightly in front of female characters. Among supporting characters like Harper’s son (Charlie Plummer) and Brenda’s husband, Tom Lopez (Michael Peña), men are the ones holding guns, driving cars.

Michael Peña (left) as 'Tom Lopez,' Carolina Bartczak as 'Brenda Lopez' (center) and Charlie Plummer as 'Sonny Harper' (right). Photo Credit: Reiner Bajo

In short, while Moonfall does inject women into non-stereotypical roles as soldiers or STEM workers, the inclusion is skin-deep. Just prick your ears and realize the sheer disparity in who actually gets to speak. More often or not, you’ll be listening to men give directions or explain crackpot scientific theories—which all turn out to be true, of course.

Race: 3.75/5

Characters of color make up a significant part of Moonfall’s roster, with Black characters the most visible among them and enjoying the choicest parts. But the colorblind natures of their roles blunt any potential depth that could be plumbed from such onscreen diversity. In fact, the only references to ethnicity arrive through stray mentions of “our Chinese friends”—the Chinese government, that is—and occasional spoken Mandarin between Fowler’s doe-eyed nanny and her young charge who happily responds in turn, the two of them sharing a secret “code” of sorts. (Why yes, this film was indeed co-produced by Chinese conglomerate Huayi Brothers Media. What gave it away?)

I’d be inclined to give this category a higher score, thanks to Fowler’s well-written character arc. Unfortunately, Moonfall trips into some extremely tired territory. While the film’s overall body count skews white—five characters to the three men of color who kick the bucket—the first to do so is a Black man, sucked into the gaping maw of outer space. (Dear Hollywood, we are not nearly past the point of letting the Black guy die first without warranting a heartfelt eye roll.) The most ignominious death, replayed three times for the audience in case we missed it the first two times, is a Black man whose face gets punched in by an alien’s limb. Finally, it’s super frustrating that the only ostensibly Latinx character we get, Brenda’s second husband Lopez played by Mexican American actor Peña, dies a “noble” death to save his white family. This one feels particularly cringeworthy, as Latinx make up, by far, the most underrepresented ethnic group in American films and TV. And no, introducing a positive character like Lopez—only to kill him off—does not count as “good representation.”

Deduction for Disability: -0.50

Houseman’s mother, played by Kathleen Fee, has dementia and sits in a manual wheelchair, needing to be pushed by a nurse to get anywhere. She’s uncreatively turned into a helpless symbol for her son’s emotional journey. Houseman himself has irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and “debilitating anxiety,” as he describes it, and pops anti-anxiety pills throughout the film. All of this played for lackluster chuckles. And to follow one of disability representation’s longest standing tropes, Houseman eventually sacrifices himself to save nondisabled characters (and the world).

Thankfully, we do see one instance of a disabled character who is a bit more normalized. Donald Sutherland enjoys brief but empowered scenes as Holdenfield, a retired NASA employee whose conspiracy theory turned out to be right all along. His agency is emphasized by his use of a motorized wheelchair.

Deduction for Age: -0.25

Women over 60 are infantilized through Houseman’s mother (detailed above), as well as a brief joke that relies on a woman, who drives up to order fast food, seeming slow-witted and blinking confusedly through thick glasses for a low-hanging laugh. She’s played by Jane Gilchrist, listed only as “Old Lady” in the credits.

Mediaversity Grade: C+ 3.25/5

The surface-level diversity in Moonfall is executed better than in most action movies, particularly through the central role that Berry plays with elegant authority. But at the end of the day, Emmerich’s film still worships at the altar of white male “mavericks.” This damaging practice, which plagues the action genre, exacerbates real-world delusions that white men are somehow under attack. “I know what it’s like to try and tell people something and have no one listen to me,” the conventionally beautiful and muscled white male lead, Harper, says to Houseman—another white man—with a straight face. Sutherland’s Holdenfield reinforces this false notion: “Anyone who follows orders [has blood on their hands],” he says knowingly to Fowler.

At face value, Moonfall’s hokey validation of even the wildest conspiracy theories—the moon is falling! It’s a “superstructure” built by ancient humans to serve as a type of Noah’s ark! Technology will destroy us all!—can genuinely be considered just a bit of fun. But when compared with real-world conspiracy theorists, who aren’t joking about vaccinations being a government ploy or stolen U.S. elections, Moonfall’s familiar refrains suddenly seem less benign. “It’s better to be forgiven than to ask permission,” Houseman repeats, twice within the film. But is this really the message we want to be telling viewers ad nauseam, movie after movie?